Words by Roxy Bourdillon

For the latest edition of LGBTease: Queeroes Of Burlesque, we share the incredible true story of a groundbreaking performer who challenged transphobia and racism way back in the 1960s.

CW: transphobia, racism

Lady Java was a trailblazer in so many ways. As one of the first out transgender women of colour in showbiz, she paved the way for countless other performers. As a captivating dancer and cabaret entertainer, she delighted audiences with her razzle-dazzle, while simultaneously challenging their preconceived ideas about gender. As a tireless activist who refused to accept transphobic and racist discrimination from the authorities, she was a vital figure in the ongoing movement towards equality. This is her story.

Spoiler alert: I think you’re going to love her.

Born in New Orleans in the 1940s, Java transitioned at a young age. She was close to her mother, who was always loving and supportive. After graduating high school, Java worked in fashion and hat-making. Her devotion to millinery continues to this day and she’s rarely seen without a chic, statement hat angled just-so.

In her 20s, Java relocated to Los Angeles and was spotted waiting tables at a nightclub. In a recent interview she recalls how she got her first big break: “Gertrude Gibson stops and says, ‘Hey pretty,’ and I said, ‘Me? Pretty?’ She says, ‘Why don’t you come on stage? Can you wear a bikini?’ I started dancing and before you know it the house was packed.”

Quickly becoming one of the leading lights of LA’s nightlife scene, Java performed alongside A-listers like Richard Pryor, James Brown and Sammy Davis. Her act included erotic dancing, go-go, singing and comedy. Although she lived as a woman, she was advertised as the “female impersonator, Sir Lady Java”. At one of her favourite hotspots, the Redd Foxx Club, she was on the bill as, “The Prettiest Man on Earth”.

Java’s decadent aesthetic was inspired by showgirls of the past. “I try to look like Lena [Horne], walk like Mae West and dress like Josephine Baker.”

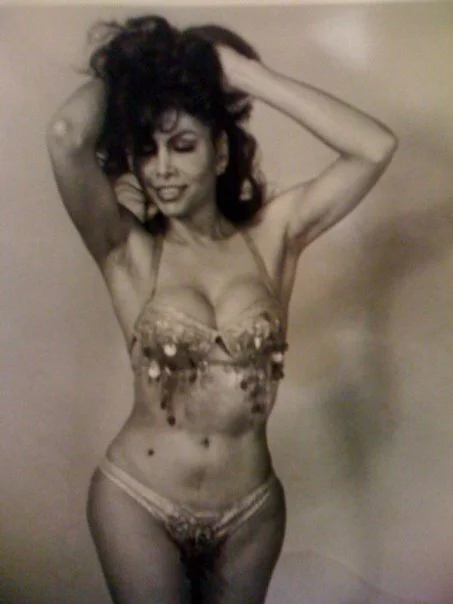

Her costumes were flawless, the stuff of your wildest fashion fantasies. We’re talking bejewelled bikinis, feather-trimmed gowns, extravagant headdresses and towering blonde beehives. No-one did too-glam-to-give-a-damn like Lady Java.

She had a fondness for travelling in style and often rode in a limo to visit the grocery store. And if you’re wondering about the origin of her stage name, one day when she was out and about a man began flirting with her. His chat-up line? “Ooh, you look like java, baby - deep, dark and delicious.”

Unfortunately not everyone was such an adoring fan. In fact, the LA police department continuously harassed her and tried to destroy her career. One night while she was dancing onstage in a sparkly bikini, being fabulous, bringing the house down, the cops showed up. They interrupted her performance and told her, in no uncertain terms, that she would only be allowed to resume her number if she wore at least three “male articles of clothing”. So then and there, she pulled on a pair of rolled-down socks, a wristwatch and a bow tie. Naturally, she kept her sparkly bikini on too.

Java’s career continued to flourish with appearances on radio and TV and in magazines like JET, Ebony and The Advocate. But the LAPD would not leave her alone. It all came to a head in autumn 1967, when Java had just finished a two week run at Redd Foxx’s club and was looking to extend it. The cops decided to put a stop to this by enforcing the decades-old “Rule Number Nine”. This cruel law banned people from “impersonation, by means of costume or dress, of a person of the opposite sex”. They threatened to fine clubs that booked her, jeopardising her livelihood and rolling back rights for her and other trans and gender-nonconforming folks.

There was a racist element at work here too. It’s no coincidence that they targeted her, a woman of colour, at the Redd Foxx Club, one of the few Black-owned venues in the area. Utterly appalled, Java gathered 25 friends for a public demonstration on La Cienega Boulevard, telling a reporter, “It’s got to stop somewhere and it won’t unless somebody steps forward and takes a stand. I guess that’s me.”

Java hired the American Civil Liberties Union and took her fight all the way to the California Supreme Court. Although the case was eventually thrown out due to a legal technicality, Java succeeded in attracting a huge amount of media attention.

She provided trans visibility at a time when it was desperately needed, and in 1969 after a separate dispute, Rule Number Nine was finally abolished for good.

Nowadays Java is rightly recognised as a groundbreaking icon. She was named one of the guests of honour at LA Trans Pride 2016 and there’s even a biopic in the works starring Pose actor, Hallie Sahar.

I’ll leave you with the words of the glorious Lady Java herself: